Not everything is for you

Can we stop tearing down women who write and make money?

Pillory, according to Merriam Webster, is “a means for exposing one to public scorn or ridicule.” The word originally referred to a public torture device we used to see in old cartoons. “A wooden frame with holes in which the head and hands can be locked” placed in the town square for all to see.

I thought of this recently as I scrolled through social media to see multiple authors, all women, pilloried for a variety of transgressions: Writing books with opinions some did not agree with, promoting themselves while female, or just being successful.

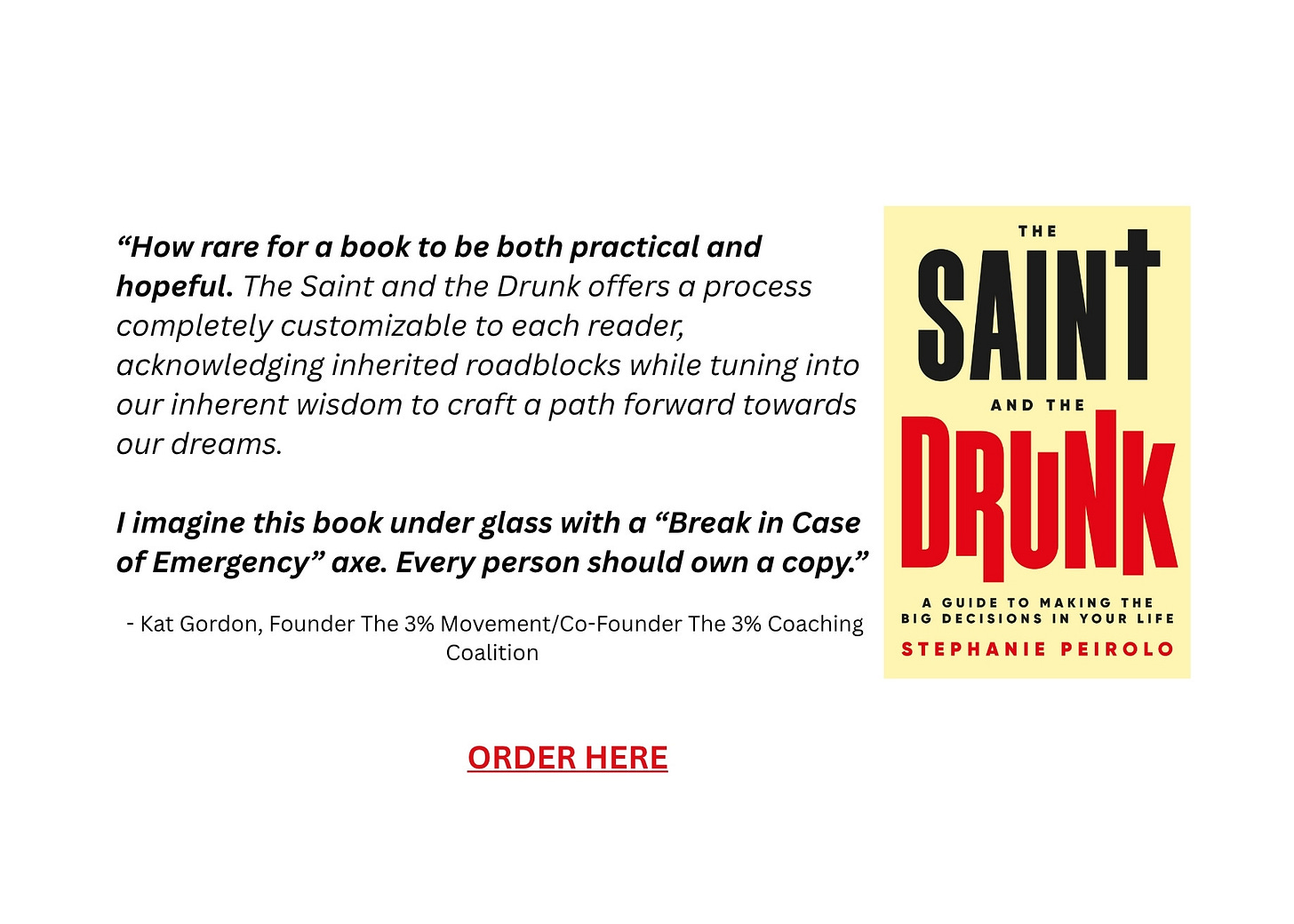

Since these books, and the women who write them are all loosely in the “self-help” genre, I paid attention. I, too, wrote a book that most classify as “self-help.” That phrase, self-help, seems to have taken on the same dismissive tang as “chick lit” – books often by and for women. The implication is that they are lesser works by nature of their target audience. No matter that women buy the vast majority of books.

And it is women who are taking to social platforms to excoriate these female authors. I’m not interested in boosting any of these signals, but there seem to be some themes.

Who does she think she is?

I don’t agree with her ideas, or I did not find them helpful, which means they are entirely without value to anyone.

Envy couched as protection of a community that does not need protection.

Who does she think she is?

If you have any hopes of selling a book, you have to promote yourself like a maniac. This is unpleasant for most. I hate it. My book has only been out seven months and I feel like book promotion has been one long root canal. I watch myself and other women authors, most of us not at all famous, shilling like three card monte players on a corner. Look at me! Here’s a palatable nugget of my findings! Here’s a distillation of my content so watered down it can fit on a carousel on social media! See me talking on a podcast! See me talking on a stage! See me! See me! Buy my book!

I’m sure we ALL wish we didn’t have to do this, or that we had big publishing dollars behind us who paid for PR or big social teams or whatever support would make it so that promoting the book wasn’t more of a time and energy suck than writing the book.

And this, our self-promotion, seems to stick in the craw of those who pillory. Who does she think she is to try to sell books, sell tickets, make a living? The outrage feels very gendered to me, a variation on the theme I’ve heard all my life and hear from my clients who are women – don’t toot your own horn. White men aren’t told that, ever. So why are we policing one another about pursuing professional and financial success for our hard work?

If I don’t like it, it has no value

Not everything is for me. If something does not resonate for me, or I don’t agree with it, I don’t have to read it. It still may work for someone else. Yes, I have seen some authors promote ideas, especially about recovery, that I don’t believe are helpful narratives. I often read things which, in my personal experience, are neither true nor supportive. But there are many things I believed or was helped by when I had two or three years of sobriety that I now see as foolishness. They still helped me.

Marianne Williamson’s book A Course of Miracles was all the rage in recovery circles when I was in early sobriety. I read the book, didn’t find it especially helpful, but I noticed she said trees had auras. I was living in a rural area at the time, and I remember taking a walk and squinting my eyes to see if I could see the auras of the trees around me. And I imagined I could, a slightly wavy outline surrounding the tall evergreens lining a path in the sharp winter morning.

I no longer look for auras on trees, but was it harmful for me to feel a connection to nature at that time in my life, to look for the sacred in the natural world? No. And I’ve known people who found that book to be very helpful, even instrumental in their spiritual path and recovery. The fact that it wasn’t a big deal for me doesn’t mean it couldn’t be helpful to others.

Envy

I fully and freely admit to a burning envy of the fame and success other authors have, especially those writing about some of the same themes I write about. But my envy is my problem, not theirs.

Some of the social media screeds imply that the successful authors are con artists, foisting foolish ideas or pseudo-science onto an incompetent and unsuspecting audience. Of other women. I have a bit more faith in our power to decide if something has merit for us personally. No one made me arbiter of value or worth. I trust women to decide what is right for them.

When Glennon Doyle joined substack this year with a subscription offering, she was wildly successful. And pilloried for it by other substack writers. I assume many of those complaining, had, like me, been laboriously piling up tiny groups of subscribers over an extended period of time. Doyle left substack shortly thereafter. Whatever the reason for her departure, the vitriol over celebrities joining substack and doing well there was remarkable. Not surprising but interesting.

Success is not a pie. A bigger slice for someone else does not mean less for me.

None of these people who seem propelled by envy ever admit to envy. No, they tout motives like protecting poor defenseless readers from exploitation, speaking truth to power, calling out something, or protecting social media platforms. News flash – social media platforms inspire controversy to monetize more outrage and need no “protecting.”

What I look for

I do, however, use some guidelines for myself in assessing the work of other authors. I also try to adhere to these in my own work and promotion as a “self-help author.”

Does this author have authority? Do they wield it responsibly?

Authority can come from education, research and data in a peer-reviewed academic setting, certification by reputable entities with guidelines that include ethical standards, or lived experience. I gravitate towards authors who check one or more of these boxes.

Are they suggesting actions that are clearly exploitative and/or immoral?

I think of a writer who wrote a book and then started a group that provided an online support system for recovering alcoholics. I get it, 12 Step Programs or other approaches to sobriety aren’t for everyone.

I want to be open to any way people can, you know, not die of alcoholism and drug addiction. But the online support group this author started was expensive and, when I looked, slim on data or evidence-based methodology.

Which seemed curious when anyone can jump online or drive to a local church basement and find 12 Step support groups for free. Free. When nice people offer help with no profit motive is it ethical to charge sick people for something very similar?

Are they accountable to a community?

Certification or education isn’t just about credibility; it’s also about accountability. I am a certified executive coach and a member of the International Coaching Federation. That means if I behave in a way that is contrary to the ethics of the group, I am accountable.

I didn’t want to get my certification, and I waited a number of years. When I got it, I didn’t learn much I hadn’t learned in graduate school, but I did meet some good people who I am still connected to, years later. We meet regularly and talk about issues that come up in our coaching work. It is guidance, support and accountability.

I write about spirituality. I am a member of a religious community as an Associate of the Sisters of St Joseph of Peace. Which means as I write about spirituality I am in community with a bunch of nuns who know way more than I do about spirituality. Which keeps me humble. I’m hardly going to play guru when I hang out with women who remind me I’m still in spiritual high school.

Both things can be true

I can agree with some of what an author writes and disagree with other things. It’s not a binary. I can choose not to engage with books or content that I don’t agree with, and it doesn’t make it wrong.

I’ve never been entirely comfortable with the way Brene Brown’s work on vulnerability and authenticity is interpreted to mean bring your authentic self to work. I’ve not been safe to bring my authentic self to work. And many people in marginalized communities aren’t safe to bring their authentic selves to work. That does not mean that Brown’s work isn’t valuable to some, or valuable in other contexts.

Build up rather than tear down

There are many many authors doing important work who aren’t superstars. Buy their books. Read them. Support them.

Two books on my reading list right now are Uncompete, Rejecting Competition to Unlock Success by Ruchika Malhotra about how competition is harming us and we should reframe our narratives and Jodi Ann Burey’s new book Authentic: The Myth of Bringing Your Full Self to Work. Shout out to Seattle authors!

Speaking for all of us not-rich-not-famous-working-our-asses-off-to-promote-our-books women, buy our books. Post about them on social media. Drop a review on Goodreads or Amazon or wherever you get your books. Choose us for your book club. I’ll come to your book club. Build us up rather than tearing down the ones who have already made it.

Because the kind of envy and resentment that leads to excoriating women who are succeeding can become a kind of torture of its own. You don’t want to be stuck in the public square, head and hands locked into a cycle of condemnation of people you disagree with or envy. Supporting emerging authors rather than tearing down existing ones might not get you as many comments, but it might free you in other ways. And we will certainly appreciate the support.